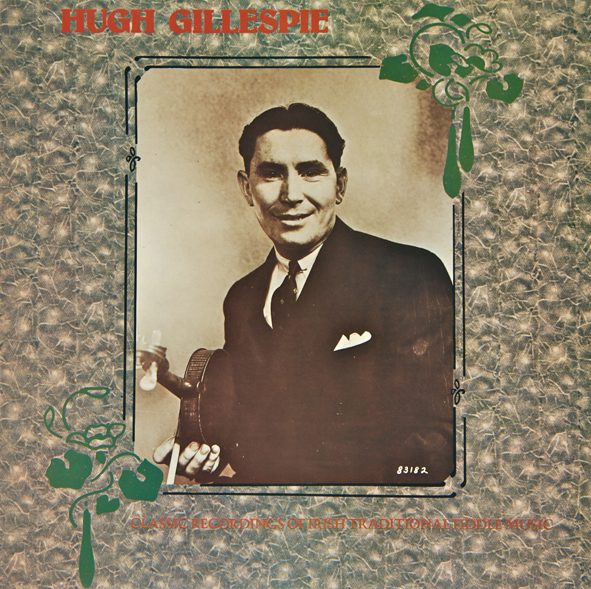

Hughie Gillespie (1906-1986)

Sleeve notes by Tony Engel and Tony Russell for the 1978 LP on Topic, Hugh Gillespie: Classic Recordings of Irish Traditional Fiddle Music (accompanied by Jack McKenna or Mark Callahan, guitar).

America in the middle ‘30s was a renewed and optimistic place; the Depression was fading, and agriculture and business were picking up. One in particular of the industries almost strangled by the Depression, the record business, was quickly regaining its momentum, not only bringing new personalities to the nation’s Victrolas, radios and newspapers, but developing its acquaintance with the musics of ethnic minority groups. Virtually every major record company had separate catalogues for the Mexican, German, Scandinavian and other relatively unassimilated communities. (Not to mention the substantial minorities catered for by the ‘hillbilly’ and ‘race’ catalogues.)

Among the richest of these communities, in terms both of musicians and of people who would pay to hear them, were the Irish-Americans.

Michael Coleman (1891-1945), probably the most famous traditional Irish musician of all, made his name on American stages and American recordings. Among his contemporaries were many other fine Irish-American musicians: Paddy Killoran, James Morrison, Frank Quinn, Dan Sullivan, John McGettigan, the Flanagan Brothers – and one of the greatest traditional fiddlers of all time, Hugh Gillespie. The tracks on this record, from original recordings of 1937-39, demonstrate a peak of musical achievement rarely attained elsewhere.

Hugh Gillespie was born on September 7, 1906, near Ballybofey in Co. Donegal, Ireland. His father was no mean musician, but it was his uncle Johnny, reckoned as among the great fiddlers, who had the deepest influence on him. Hugh started playing as a small boy, and performed regularly in his locality while he was growing up. When he was about 20 he became involved in sheep-dealing and, at the same time a disagreement with his father, who claimed that Hugh’s sheep were taking pasture away from his cattle.

On February 4, 1928, Hugh left Donegal for New York, to follow the path that many of his countrymen had already trod and to make enough money to be able to return and set up on his own, (In this he succeeded, and it was at his farm back home in Ballybofey that we interviewed him for these notes, in September 1977.)

On arriving in New York Hugh went to stay with his uncle. Upstairs in the house lived Neil Smith, who played bones in the band headed by fiddler Packie Dolan. Smith had a few records of the already celebrated Michael Coleman, and immediately Hugh heard them he wanted to meet their maker. In fact, he had not been in New York four days before someone took him round to Coleman’s and introduced him. Coleman asked Hugh to play for him almost at once. After hearing him, he said: ‘You and I are going to be together, because I’m taking you under my wing.’

Coleman was true to his word, and the next few years were a busy time for the younger man. His regular job, as an engineer at Consolidated Edison, didn’t prevent him broadcasting daily with Coleman on local radio stations, such as WRL, WINS, WBNX, WRD, WFAB and WHOM. The programmes, usually called something like ‘The Irish Hour’, would commonly be sponsored by clothing and furniture companies and would be divided about 50-50 between music and ads.

The two fiddlers played without any accompaniment. They would fill numerous requests, which, Hugh recalls, came scarcely ever from Irish people but from nearly every other nationality represented in New York. Payment for these programmes was union scale, $55 an hour per person. It was impossible at that time, says Hugh, to broadcast, record or play in dance halls if one was not a union member.

As well as his time with Coleman, Hugh Gillespie had spells with various bands over the years, chiefly groups led by his cousin, Jim Gillespie, who played button accordeon. These included such bands as the Star of Erin Orchestra and the Four Provinces Orchestra (not to be confused with the similarly named group of a few years before, which was led by Ed Reavy and worked out of Philadelphia).

The normal venues for such bands were cabarets (licensed clubs). One of the Four Provinces Orchestra’s regular spots was in a Polish section, where the Varsovienne and Mazurka were in great demand.

Gillespie made his first recordings in New York in May 1937. He had earlier accompanied Coleman to one of the older man’s own sessions and been introduced to the studio manager. ‘I’d like you to hear him play,’ said Coleman. The demonstration was a success, and a formal recording session was scheduled within a week.

Four sides were recorded, Master Crowley’s Reels, The Irish Mazurka, The Mullingar Lee/The Star of Munster and McCornick’s Hornpipe, of which the first two are included on this record. Gillespie is accompaniedon guitar by Mark Callahan, a neighbour who occasionally played with him on radio. Callahan had some trouble tuning his guitar at the session and Gillespie, worried that he might break a string, suggested they tune to a full tone below concert pitch, which they did.

Most Irish musicians at this time were using piano for backup, but Hugh felt that the tone of a guitar suited fiddle music better. He seems not to have been alone in this feeling, for both Coleman and Paddy Killoran, on some of their records of the middle and late ‘30s, used guitar accompanists.

Gillespie’s subsequent sessions, in June 1938 and June 1939, produced eight sides each, all of which are included on this record except the reel selection The Pigeon on the Gate/The Lady of the House and the hornpipes The Stage/Rights of Man, (both from the 1939 session). On both of these occasions he was accompanied by guitarist Jack (John) McKenna,

a partnership that generated some of the finest traditional music on record.

McKenna is the ideal foil for Gillespie: while his choice of chords does not always conform to strict standards of musical correctness, he does provide a percussive rhythm that is exceptionally exciting.

According to Gillespie the 1938 and ‘39 recordings were made at concert pitch, but this does not seem to be true of the former session, since achieving this pitch on playback requires a playing speed of well over 82 rpm. In those days recording speeds were not entirely stable and could vary for a number of reasons: for example, the cutting lathe could alter

in speed as it warmed up in the course of a session.

It would seem that the 1938 sides were played a semitone below concert pitch (which accords with a playback speed close to 78 rpm). The final session was definitely in concert pitch. Hugh remembers that on one session McKenna broke a string and played

on the remaining five throughout, and although he cannot be sure that this was at the ‘38 session, it does seem likely, and may account in part for the choice of pitch.

It was always a good idea to devise tune titles that had not previously been used on record, so that anyone ordering a piece by its title would be sure to get just that, and not somebody else’s version of a tune with the same name. Some tunes were named after music-lovers whose houses were always open to musicians to gather and play; hosts like Con Crowley, Paddy Finley and Dick Cosgrove.

There were in fact two such Crowleys: Gillespie dedicated a couple of his recordings to one of them, while Coleman’s Crowley’s Reels were for the other (and are different tunes from those on Gillespie’s first record). In the selection Jackson’s Favorite/Kips the latter tune was named after the Sligo fiddler Kippeen Scanlon, from whom it came.

The recordings of Hugh Gillespie have aquite different ‘feel’ from other American-Irish fiddle music of the period. The somewhat unusual choice of guitar rather than piano for accompaniment certainly contributes to this distinctiveness, but probably the decisive factors are Gillespie’s ‘singing’ style and highly personal technique. He learned from Coleman a device he calls ‘back trebling’, and also uses drones and fractional flattening or sharpening of notes to great effect. Such techniques are by no means peculiar to Coleman or Gillespie – indeed, most Irish musicians use them in some degree – but every musician stamps them with his own particular emphases.

In these recordings of Hugh Gillespie at his peak, the sum of these various elements is a unique and outstanding series of performances.

Alan Morrisroe has kindly donated his collection of Hughie’s Decca label gramophone recordings.